Executive Summary

YouTube’s recommendation system is a crucial element to its business practice. The recommendation system is implemented both on its website and on its mobile app, recommending videos that users may be interested in based on a number of factors related to the user, the video, the watching context, and more.

YouTube has recently announced that it will make improvements to its recommendation system; however, this announcement is only one of many that have been made addressing the same persistent issue of polarizing, radical, or otherwise offensive content on YouTube. YouTube did not specify which changes will be made, nor did it directly address many public misgivings that led to this announcement.

The purpose of this report is to explore YouTube’s recommendation system and its historical and present negative impacts on users. Through this exploration, this report will offer recommendations on how to mitigate the amount of potential harmful material reaching unintended audiences. The recommendations offered will be both specific to the recommendation system model and qualitative/structural. This report finds that without active, willing, and proactive movement, harmful and unintended content will often reach the wrong audiences.

Key Findings:

- YouTube’s recommendation system falters under the ‘visitor cold start problem’.

- The ‘visitor cold start problem’ is the situation in which a new user enters a website. Recommendation systems in place at YouTube are not able to contextualize new users, recommending extreme/ideological content early on.

- The currently used ranking metric of a video’s relevance is often insufficient.

- The metric used is ‘watch time’, which boosts videos that contain addicting content. In theory, this should boost original content by creators but rather ends up encouraging/promoting potentially harmful material.

- The changes made by YouTube to combat offensive content have been largely successful, but due to content removal rather than recommendation system improvement.

- Multiple random walks no longer result in videos at the level of Elsagate, but offensive material still slips through the cracks.

Recommendations:

- Increase transparency regarding the model.

- YouTube has claimed it has made multiple changes to the way its model is designed, yet it has not specified exactly what changes were made at which point.

- Encourage collection of explicit ratings.

- Rather than relying on inference from implicit ratings, encourage users to provide explicit ratings to use as a basis for modeling.

- In general: steps should be taken to reduce the possibility of feedback loops.

- Consider policy/structural changes to address undesirable recommendations and content.

- As an example: YouTube Kids pulls from the same pool of videos as YouTube. Reduce the risk of low-quality content by making YouTube Kids a separate creating platform.

- In addition: consider explicitly stating that politically polarizing, at times offensive and anti-minority videos that still fall within the community guidelines are types of material that YouTube wants to recommend less.

Introduction

YouTube boasts almost two billion logged-in users per month.[1] Additionally, about 8 out of 10 18-49 year olds watch YouTube (as of April 2016).[2] One of YouTube’s primary sources of revenue is advertisements and thus, similar to other content-oriented websites, the company highly values online time. YouTube’s recommendation system is a crucial element of its business practice, keeping users engaged by recommending videos based on a variety of factors ranging from information about the user, information about the video, information about similar users and videos, the context of each watch, and beyond. This recommendation system is responsible for more than 70% of users’ time spent on YouTube.[3]

YouTube’s recommendation system, in the words of the company, “at [its] best… help[s] users find a new song to fall in love with, discover their next favorite creator, or learn that great paella recipe.”[4] At its worst, it has recommended graphic, perverted material to children,[5] far-right conspiracy theories regarding national tragedies,[6],[7],[8] and deliberate misinformation regarding commonly considered scientific and historical truths.[9] These negative user experiences with recommendations have been consistently brought to the company’s attention since mid-2017,[10] resulting in a series of content filtering and app changes on the part of the company.[11],[12],[13]

Most recently, on January 24, 2019, BuzzFeed News released a report titled “We Followed YouTube’s Recommendation System Down the Rabbit Hole”,[14] in which it ran multiple search queries in a private browser and followed the video recommendation chain. Many of these queries led to politically extreme, pirated, or otherwise unrelated content.

In response, YouTube released a statement on the following day indicating that they will “begin reducing recommendations of borderline content and content that could misinform users in harmful ways—such as videos promoting a phony miracle cure for a serious illness, claiming the earth is flat, or making blatantly false claims about historic events like 9/11.”[15]

Over the years, YouTube has indeed made changes, many times significant. This report finds, however, that Buzzfeed News’s story from January 24 is best explained as a continuation of similar issues that have plagued YouTube’s recommendation system since 2017. Despite the changes that YouTube has implemented in the past, these issues persist, and without the correct steps, may continue to occur.

This report will begin by providing a an explanation of YouTube’s specific implementation of recommendation systems. A brief history of demonstrated issues with YouTube’s recommendation system will follow. Finally, this report will conclude with recommendations, both algorithm and policy specific.

The Recommendation System

All of the information specific to YouTube’s recommendation system in this section is taken from the 2016 paper, “Deep Neural Networks for YouTube Recommendations” by Paul Covington, Jay Adams, and Emre Sargin.[16]

YouTube’s recommendation system can be described as a deep learning generalization of traditional matrix factorization techniques. Deep learning is a subset of machine learning, which is a field of artificial intelligence that uses structured data (features) to make predictions. Deep learning is generally used in lieu of traditional machine learning techniques because it can learn features from raw data instead of requiring designed features.

Recommendation systems, as the name suggests, are designed to recommend items to users based on various characteristics of the user and the item. There are two main types of conventional recommendation systems: Content-based and collaborative filtering. Content-based filtering recommendation systems recommend items to users based on attributes of the item. Collaborative filtering recommends items to users based on users’ similarities to each other. Matrix Factorization is a collaborative filtering approach to recommendation systems.

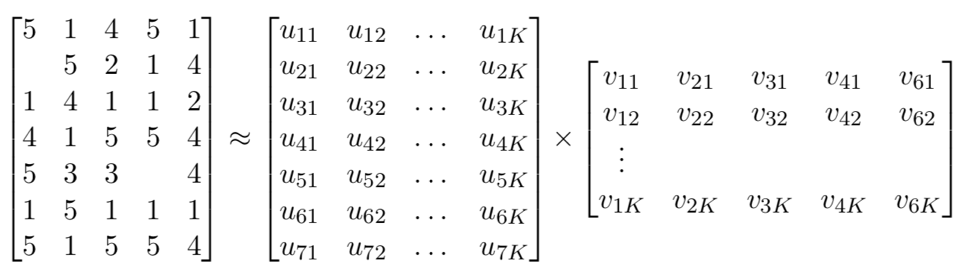

In machine learning, a common problem is encoding and embedding (or representing) non-numeric characteristics. Within the specific context of recommendation systems, modelers must find how to best represent the numerical abstractions of a user and an item. In general, matrix factorization can be described as deriving (“factoring out”) these user and item embeddings from a matrix of ratings. Consider the following:

On the left side hand of the above example is the ratings matrix. This is a collection of ratings that users have given the items. On the right hand side are the user matrix (on the left, with the u terms) and the item matrix (on the right, with the v terms). Both of these matrices are unknown; the purpose of matrix factorization is to find the best user and item embeddings that fit the ratings matrix on the left-hand side.

In the example above, we have 7 users and 6 items. Each of these users and items have K characteristics in their embeddings. For example, the embedding of User 1 can be given by the first row of the user matrix: the vector of numbers u1 = [u11, u12, u13, …, u1K] where the first subscript indicates the user (stays constant, as this vector contains characteristics of the same user) and the second subscript represents the characteristic. The same logic applies to the matrix of items (v), except each item is represented by a column rather than a row.

On the left-hand side of the above example is the matrix of ratings. Consider each row to be a user and each column to be a vector. As such, User 1 has rated Item 1 with a 5, User 3 has rated Item 5 with a 2, and so on. In this example, User 2’s rating of Item 1 and User 5’s rating of Item 4 are missing, indicating that these users have not yet consumed those items. In order to make predictions for these missing ratings, a model must be built that estimates the user and item embeddings so that the resulting ratings matrix from their product very closely resembles the given ratings matrix. Once satisfactory embeddings are found, we can then make predictions on the missing ratings by substituting in the corresponding results of the product of the user and item matrices.

In practice, the ratings matrix is often what is considered sparse, meaning that there are many empty values. This sparsity is due to a lack of ratings. Consider the average YouTube user; of total videos watched, the user has probably ‘liked’ or ‘disliked’ (rated) a small percentage. When implementing recommendation systems, modelers must often choose how to handle sparsity. YouTube has decided to use implicit ratings; if User 1 has seen Video 1, their rating is considered to be a positive, encoded as a 1. If User 2 has not seen Video 2, their rating is considered to be negative/neutral, encoded as a 0.

One key component of matrix factorization is that it allows for a representation of users and items so that they can easily be clustered. Like the name suggests, clustering is a way of grouping points of data. User embeddings that are within short distances to each other (as vectors are N-dimensional representations of points in space) will be similar; crucially, this allows for similarity analysis between users and between items, compatibility, etc. If a new item is introduced and a user watches it, this item can easily be recommended to other users due to this clustering. New users, however, cannot be easily clustered; as such, new users (the ‘visitor cold start problem’) are not handled well by matrix factorization.

YouTube’s recommendation system displays similar strategies as matrix factorization but used within a deep learning framework. Though YouTube still had to hand-engineer many features, one advantage of using deep learning in complex cases such as YouTube’s is the ability to add features in addition to the user and item embeddings. Through deep learning, YouTube also takes into account search history, demographic features, age of video, etc.

YouTube’s deep learning model is comprised of two layers of neural networks, which can be described as a collection of communicating machine learning algorithms. The first layer is the candidate generation layer, where a list of possible suitable videos is compiled, and the second layer is the ranking layer, where the list of possible videos is ranked in order of interest to the user. The candidate generation layer can be roughly explained as a generalization of the matrix factorization technique while incorporating other features previously mentioned.

The ranking system is architecturally similar to the candidate generation network, but more features are able to be used as the corpus of videos to pull from is much smaller than that of the candidate generation layer. Scores are assigned to each video based on expected watch time per impression. Click-through rate was specifically not used in order to avoid the popularity of ‘clickbait’ videos.

Key findings can be found below:

YouTube’s recommendation system falters under the ‘visitor cold start problem’.

Collaborative filtering techniques are particularly subject to the visitor cold start problem. When a new user is introduced, there are no other users with whom to compare embeddings. Users are recommended videos with barebones features – likely just geographic location along with a couple of other non-hyperspecific features. Additionally, the recommendation system can feed into itself – once one politically extreme video is watched, more are likely to be recommended.

The currently used ranking metric of a video’s relevance is often insufficient.

The ranking layer of the deep learning model used by YouTube ranks based on predicted watch time. Though a decent indicator of a video’s relevance to a user, the high value placed on this metric has led to the same effect Covington, Adams, and Sargin wanted to avoid by using watch time rather than click-through rate. Indeed, attention grabbing headlines and political content still are recommended highly by the system.

A Brief History of Issues and YouTube’s Responses

YouTube’s history with harmful content tied specifically to its ‘algorithm’ began in mid-to-late 2017. These emergent issues were regarding graphic videos targeted at children[17],[18] and far-right conspiracy theories.[19] After adjustment by YouTube, these problems later evolved into less extreme but still persistent issues with polarizing or otherwise inappropriate content.[20]

Children-targeted graphic content

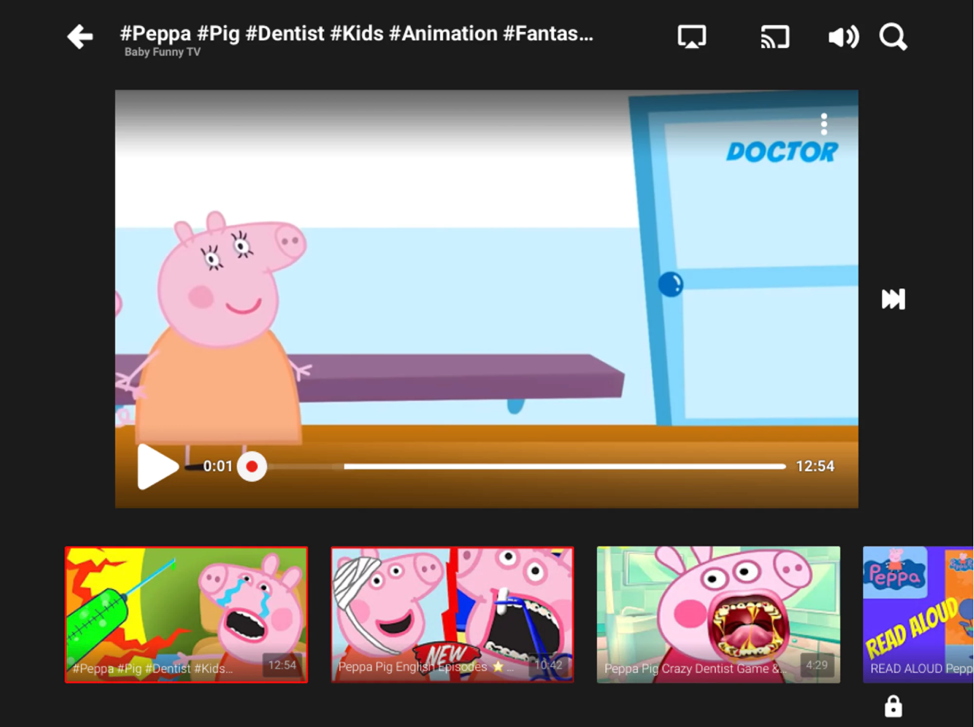

Late 2017 marked the peak of criticism of disturbing, at times violent or sexual material on YouTube targeted towards children. This corpus of content was largely categorized as “Elsagate”,[21] in reference to the seemingly innocent source material such as Elsa from Disney’s Frozen that would draw in presumably child viewers. Though these videos often appeared innocent from either thumbnails or descriptions, at certain points they would turn to graphic, adult-themed content. In one instance, knockoff characters from PAW Patrol, a popular animated series on TVOntario and Nickelodeon, drove directly into a light pole and burst into flames.[22] Further cases saw characters from Peppa Pig, another popular children’s animation, mugging a young girl with a knife and gun[23], drinking bleach,[24] and violently getting their teeth pulled,[25] among other vulgarities. Though these sorts of videos have existed since at least 2014,[26] Elsagate was amplified through what was commonly referred to as YouTube’s ‘algorithm’. Many of these video recommendations were made in YouTube’s main site/app, but many also occurred in YouTube’s children’s version called YouTube Kids. Below is a screenshot of recommendations made in the YouTube Kids app from The Outline, captured in March 2017.[27] Please be warned, the imagery is disturbing.

YouTube Kids was released in February 2015 with the purpose of consolidating parental controls, kid-oriented design, and family friendly content.[28] Despite its founding purpose, disturbing content was still being recommended to children on the children-specific app. YouTube Kids is not a separate platform for creators but is rather a separate platform for consumption of material. The pool from which YouTube draws its recommendations is the same as that of its full site, merely employing a separate filtering methodology.[29] Nina Knight, a manager in communications and public affairs at YouTube told The Atlantic in July 2017 that “the available content is not curated but rather filtered into the app via the algorithm”.[30] YouTube relies on a combination of its recommendation system and parents to filter and flag offensive content.[31]

Offensive content still persists, especially on the YouTube main site, but the issue of inappropriate recommendations has been highly mitigated. During the course of this report, I performed many random walks from various starting points within children’s content and came across explicitly inappropriate content on occasion on the main site and 0 times on the YouTube Kids app. The inappropriate content I came across on the main site was not on the same scale of violence as previously described but still disturbing, featuring thumbnails of tombstones and dead characters, characters getting drugged, etc.

Though YouTube Kids recommended no explicitly inappropriate videos, the recommendation system has not succeeded in filtering out low quality videos. In one example of many types of videos recommended on YouTube Kids, characters from the film Cars eat apples from a tree, get poisoned, and then sent to jail.[32] Little to no words are used, as the sound is either just recordings of nursery rhymes or sound effects. Many of these videos have millions of views and are from unverified channels.[33] YouTube’s response to the crisis of inappropriate children’s material has been centered around removing offending videos. In this effort, they have employed human review teams, external evaluators, and machine learning techniques to identify and remove offensive material beforehand.[34],[35],[36] To their deserved credit, they have been largely successful in removing offensive material; however, little has been mentioned in terms of actual tuning of recommendation systems. Though content control and recommendation go hand in hand, content control alone cannot fix the issue of bad content, as indicated by the remaining inappropriate content recommended on the main site. The root cause of complaints, the inability for YouTube’s recommendation system to identify low quality content, has not been addressed.

Extreme political content

Parallel to the growth of Elsagate content was the growth of far-right conspiracy theories. Following the 2017 shooting in Las Vegas, in which 58 people were killed and hundreds injured, YouTube recommended videos with headlines such as “Las Vegas Shooting Full of Holes” and “Las Vegas Shooting… Something’s Not Right!”[37] Similarly, following the Parkland massacre, videos describing as ‘crisis actors’ were also recommended.[38] In response, YouTube started a series of public updates on how it was acting to combat extremist content. Again, its approach was centered around removal of content using machine learning and human teams but did not acknowledge the recommendation systems at the heart of the public complaints brought against them.[39] Data & Society conducted random walks starting from 1,356 channels from across the political and entertainment spectrum and created clusters of similar topics based off their recommendation paths.[40] This study indicated that YouTube clustered general conservative media with far-right media (including anti-feminist, alt-right, and conspiracy theory groups), implying that any conservative viewer on YouTube is only a couple clicks away from extreme far right channels. Alex Jones of InfoWars, a conspiracy theorist and Sandy Hook denier, was a common node to the conservative and far-right channels until his removal from the site in August 2018.

Though less blatantly extremist content can now be as easily found on YouTube, a similar version of the same problem persists. Buzzfeed News’s report indicates that YouTube still has a problem with recommending politically polarizing, attention drawing videos. Titles recommended include “Snowflake Student tries to bait Dinesh D’Souza on immigration, Gets SCHOOLED instead”, “DIGITAL EXCLUSIVE: Bill O’Reilly Warns Against A RISING EVIL In America | Huckabee”, and titles containing QAnon references and catchphrases.[41] Pew Research indicates that YouTube’s recommendation system directs users towards longer and more popular content; indeed, many of the videos referenced in the Buzzfeed News article are over 13 minutes long and have millions of views.[42]

YouTube’s response to the Buzzfeed News piece marked the first time the company has explicitly mentioned addressing the spread of undesirable content rather than its existence itself. Yet, it is unclear what kind of content YouTube considers to be undesirable – in its statement, it only lists pseudoscience, flat-earth theory, and 9/11 trutherism as examples of content it wants to recommend less. In addition, YouTube considers this content as within the community guidelines and as such, will not actually be deleted.[43]

Still, far right material on YouTube persists and exists within an ecosystem based on engagement and boosting recommendation scores.[44] Many of these far-right views are white-nationalist, anti-feminist, and/or transphobic; yet, because they fall within the community guidelines, are still considered legitimate content.

In both cases of the children’s material and political material, content limitation has solved many of YouTube’s woes; however, where content lies within the community guidelines, recommendation systems must perform better. Though content limitation and filtering has reduced the number of problematic recommended content, the original concerns raised were in regard to the performance of the recommendation system. These concerns have not been publicly addressed until January 25. It is additionally unclear what YouTube prioritizes as material that needs to be less recommended.

Key findings can be found below:

YouTube’s recommendation system falters under the ‘visitor cold start problem’.

YouTube’s system is not designed to handle new users very well. As demonstrated, new users, with no watch history, are exposed to potentially harmful material early on in recommendation chains. YouTube’s recommendation system seems eager to suggest ideological/otherwise harmful videos, revealing a possible problem in the way it calculates user relevance. Again, this problem exacerbates itself; once one of these videos are clicked, more are recommended.

The changes made by YouTube to combat offensive content have been largely successful, but due to content removal rather than recommendation system improvement.

In its history of public statements, YouTube has addressed issues of its recommendation system by increasing its efforts to remove offensive content. This strategy has been successful in reducing exposure to potentially harmful material; however, YouTube has not indicated that many changes have been made to its recommendation system in and of itself. Lingering problems with recommended content show the limitation of this approach.

Recommendations:

As YouTube moves forward in explicitly changing its recommendation system, some recommendations for improvement can be found below.

Increase transparency regarding the model.

YouTube does not often release material or blog posts directly referencing its recommendation system. When it does, no explicit, model-specific changes are listed.[45] The paper written by Covington, Adams, and Sargin references hundreds of features used in the model training process yet only explicitly references around 10. The features considered are important insights for the public to understand why they receive specific recommendations. These features are also crucial for the press and researchers to better understand why the recommendation system behaves the way it does, even opening potentially more powerful and efficient ways of improving the system.

Encourage collection of explicit ratings.

Either through surveys, periodic reminders, banners, or something similar – YouTube should encourage the collection of explicit ratings so it does not have to rely on implicit ratings. Implicit ratings are indirectly a measure of viralness/popularity rather than that of actual preferences. Rather than recommending material similar to that of a user’s previous watch history, potentially introducing a feedback loop, by encouraging explicit ratings, YouTube could more directly address user interests. As an example, the ‘visitor cold start problem’ is not limited to completely new users. Every visit to YouTube by the same user exists within a different context (after good/bad day at work, after run in with an old friend, after negative experience with a person of a different race). By shaping recommendation systems around explicit likes and dislikes, YouTube could offer a more consistent recommendation corpus rather than material watched during different user contexts.

Consider policy/structural changes to address undesirable recommendations and content.

YouTube has largely focused on machine learning techniques to remove offensive/low-quality content. Though machine learning techniques are useful, policy changes should also be enacted to create a safer, more neutral environment on YouTube. For example: YouTube Kids currently pulls from the same pool of videos as the main site, relying on machine learning to filter out inappropriate content. Low-quality, un-educational videos persist on YouTube Kids as they fall within the community guidelines. If YouTube were to treat YouTube Kids as a separate platform for creators by separating the corpus of videos from the main site and perhaps only allowing verified creators to upload content, the reliance on a machine learning algorithm will lower and the quality of videos should increase.

Another possible structural change is to introduce more explicit relationships between videos. As an example, Vimeo organizes its videos into topics. Instead of relying on its deep learning model to learn relationships between items, YouTube could more efficiently make relevant recommendations if videos share more explicit commonalities.

Finally, YouTube does not explicitly express interest in reducing recommendations of politically extreme, at many instances anti-minority content. Considering the polarizing, alienating, and addicting nature of this content, YouTube should explicitly state intentions to lower these recommendation scores in addition to misinformation, conspiracy theories, and the like.

–

Conclusion

Standing at the second most visited website in the world, following parent Google.com, YouTube is a crucial player in the media landscape. Though it has made large strides in reducing the exposure of disturbing, polarizing, and otherwise harmful content on its site, its recommendation system still recommends provocative material at times from hate groups.[46] After over a year and a half of public wrestling with its recommendation system, YouTube has finally announced this past week that it will take steps to reduce problems in its model. As the company moves forward in improving recommendations, introducing greater transparency, policy/structural changes, and algorithmic changes are key elements to creating a safer, more neutral online environment.

[1] Youtube for Press https://www.youtube.com/yt/about/press/

[2] O’Neil-Hart, Celie, and Howard Blumstein. “The Latest Video Trends: Where Your Audience Is Watching.” Google, Google, Apr. 2016, www.thinkwithgoogle.com/consumer-insights/video-trends-where-audience-watching/

[3]O’Neil-Hart, Celie, and Howard Blumstein. “The Latest Video Trends: Where Your Audience Is Watching.” Google, Google, Apr. 2016, www.thinkwithgoogle.com/consumer-insights/video-trends-where-audience-watching/

[4] “Continuing Our Work to Improve Recommendations on YouTube.” Official YouTube Blog, 25 Jan. 2019, youtube.googleblog.com/2019/01/continuing-our-work-to-improve.html

[5]Bridle, James. “Something Is Wrong on the Internet – James Bridle – Medium.” Medium.com, Medium, 6 Nov. 2017, medium.com/@jamesbridle/something-is-wrong-on-the-internet-c39c471271d2

[6] Timberg, Craig, and Drew Harwell. “Parkland Shooting ‘Crisis Actor’ Videos Lead Users to a ‘Conspiracy Ecosystem’ on YouTube, New Research Shows.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 25 Feb. 2018, www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-switch/wp/2018/02/25/parkland-shooting-crisis-actor-videos-lead-users-to-a-conspiracy-ecosystem-on-youtube-new-research-shows/

[7] Popken, Ben. “As Algorithms Take over, YouTube’s Recommendations Highlight a Human Problem.” NBCNews.com, NBCUniversal News Group, 19 Apr. 2018, www.nbcnews.com/tech/social-media/algorithms-take-over-youtube-s-recommendations-highlight-human-problem-n867596

[8] Warzel, Charlie. “Here’s How YouTube Is Spreading Conspiracy Theories About The Vegas Shooting.” BuzzFeed News, BuzzFeed News, 4 Oct. 2017, www.buzzfeednews.com/article/charliewarzel/heres-how-youtube-is-spreading-conspiracy-theories-about

[9]Hu, Jane C. “YouTube’s Autoplay Function Is Helping Convert People into Flat Earthers.” Quartz, Quartz, 20 Nov. 2018, qz.com/1469260/youtubes-autoplay-function-is-helping-convert-people-into-flat-earthers/

[10] LaFrance, Adrienne. “The Algorithm That Makes Preschoolers Obsessed With YouTube Kids.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 27 July 2017, www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2017/07/what-youtube-reveals-about-the-toddler-mind/534765/

[11]“More Information, Faster Removals, More People – an Update on What We’re Doing to Enforce YouTube’s Community Guidelines.” Official YouTube Blog, 23 Apr. 2018, youtube.googleblog.com/2018/04/more-information-faster-removals-more.html

[12] “Faster Removals and Tackling Comments – an Update on What We’re Doing to Enforce YouTube’s Community Guidelines.” Official YouTube Blog, 13 Dec. 2018, youtube.googleblog.com/2018/12/faster-removals-and-tackling-comments.html

[13] “Introducing New Choices for Parents to Further Customize YouTube Kids.” Official YouTube Blog, 25 Apr. 2018, youtube.googleblog.com/2018/04/introducing-new-choices-for-parents-to.html

[14] O’Donovan, Caroline. “We Followed YouTube’s Recommendation Algorithm Down The Rabbit Hole.” BuzzFeed News, BuzzFeed News, 30 Jan. 2019, www.buzzfeednews.com/article/carolineodonovan/down-youtubes-recommendation-rabbithole

[15] YouTube, “Continuing Our Work to Improve Recommendations on YouTube”

[16]Covington, Paul, et al. “Deep Neural Networks for YouTube Recommendations.” Proceedings of the 10th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems – RecSys ’16, 2016, doi:10.1145/2959100.2959190.

[17] LaFrance, Adrienne. “The Algorithm That Makes Preschoolers Obsessed With YouTube Kids.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 27 July 2017, www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2017/07/what-youtube-reveals-about-the-toddler-mind/534765/

[18] Placido, Dani Di. “YouTube’s ‘Elsagate’ Illuminates The Unintended Horrors Of The Digital Age.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 29 Nov. 2017, www.forbes.com/sites/danidiplacido/2017/11/28/youtubes-elsagate-illuminates-the-unintended-horrors-of-the-digital-age/#59e0af796ba7

[19] Warzel, Charlie. “Here’s How YouTube Is Spreading Conspiracy Theories About The Vegas Shooting.” BuzzFeed News, BuzzFeed News, 4 Oct. 2017, www.buzzfeednews.com/article/charliewarzel/heres-how-youtube-is-spreading-conspiracy-theories-about

[20] O’Donovan, “We Followed YouTube’s Recommendation Algorithm Down The Rabbit Hole.” BuzzFeed

[21] Placido, “YouTube’s ‘Elsagate’ Illuminates The Unintended Horrors Of The Digital Age.” Forbes

[22] Maheshwari, Sapna. “On YouTube Kids, Startling Videos Slip Past Filters.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 4 Nov. 2017, www.nytimes.com/2017/11/04/business/media/youtube-kids-paw-patrol.html?_r=0.

[23] Palmer, Alun, and Ben Griffiths. “Kids Left Traumatised by Sick YouTube Clips Showing Peppa Pig Characters with Knifes and Guns.” The Sun, The Sun, 10 July 2016, www.thesun.co.uk/news/1418668/kids-left-traumatised-after-sick-youtube-clips-showing-peppa-pig-characters-with-knifes-and-guns-appear-on-app-for-children/

[24] Spangler, Todd. “YouTube Moves to Age-Restrict Weird and Disturbing Kid-Targeted Videos.” Variety, Variety, 10 Nov. 2017, variety.com/2017/digital/news/youtube-kids-bizarre-disturbing-videos-blocking-age-restriction-1202611864/

[25]June, Laura. “YouTube Has a Fake Peppa Pig Problem.” The Outline, The Outline, 16 Mar. 2017, theoutline.com/post/1239/youtube-has-a-fake-peppa-pig-problem

[26] Yoo, Se-Bin. “Crude Parodies of Kids’ Movies Can’t Be Stopped.” Korea JoongAng Daily, 27 Jan. 2018, koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/news/article/article.aspx?aid=3043884

[27] June, Laura. “YouTube Has a Fake Peppa Pig Problem.” The Outline

[28] “Introducing the Newest Member of Our Family, the YouTube Kids App–Available on Google Play and the App Store.” Official YouTube Blog, 23 Feb. 2015, youtube.googleblog.com/2015/02/youtube-kids.html

[29] Subedar, Anisa, and Will Yates. “The Disturbing YouTube Videos That Are Tricking Children.” BBC News, BBC, 27 Mar. 2017, www.bbc.com/news/blogs-trending-39381889

[30] LaFrance, Adrienne. “The Algorithm That Makes Preschoolers Obsessed With YouTube Kids.” The Atlantic

[31] “Introducing Kid Profiles, New Parental Controls, and a New Exciting Look for Kids, Which Will Begin Rolling out Today!” Official YouTube Blog, 2 Nov. 2017, youtube.googleblog.com/2017/11/introducing-kid-profiles-new-parental.html

[32] Nana, Super Dolphin. “Disney Cars Mcqueen and Jackson Storm, Car Pixar Eat Poison Apple Of Miss Fritter Nursery.” YouTube, YouTube, 30 Jan. 2019, www.youtube.com/watch?v=8ZGDejEJcq4

[33] Bee, Banana. “Pronounce Shapes with Police Cars Replace Tyres – Tractor Cartoon.” YouTube, YouTube, 23 Aug. 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=eXogx7UyptA

[34] “External Evaluators and Recommendations – YouTube Help.” Google, Google, support.google.com/youtube/answer/9230586

[35] “Faster Removals and Tackling Comments – an Update on What We’re Doing to Enforce YouTube’s Community Guidelines.” Official YouTube Blog, 13 Dec. 2018, youtube.googleblog.com/2018/12/faster-removals-and-tackling-comments.html

[36] “Google Transparency Report.” Google Transparency Report, Google, 2018, transparencyreport.google.com/youtube-policy/removals?total_removed_videos=period%3AY2018Q3%3Bexclude_automated%3A&lu=total_removed_videos

[37] Warzel, Charlie. “Here’s How YouTube Is Spreading Conspiracy Theories About The Vegas Shooting.” BuzzFeed News

[38] Popken, “As Algorithms Take over, YouTube’s Recommendations Highlight a Human Problem.” NBCNews.com

[39] “Expanding Our Work against Abuse of Our Platform.” Official YouTube Blog, 4 Dec. 2017, youtube.googleblog.com/2017/12/expanding-our-work-against-abuse-of-our.html

[40] D&S Media Manipulation. “Unite the Right? How YouTube’s Recommendation Algorithm Connects The U.S. Far-Right.” Medium.com, Medium, 11 Apr. 2018, medium.com/@MediaManipulation/unite-the-right-how-youtubes-recommendation-algorithm-connects-the-u-s-far-right-9f1387ccfabd

[41] O’Donovan, Caroline. “We Followed YouTube’s Recommendation Algorithm Down The Rabbit Hole.” BuzzFeed News

[42]Smith, Aaron, et al. “Many Turn to YouTube for Children’s Content, News, How-To Lessons.” Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech, Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech, 3 Dec. 2018, www.pewinternet.org/2018/11/07/many-turn-to-youtube-for-childrens-content-news-how-to-lessons/

[43] YouTube, “Continuing Our Work to Improve Recommendations on YouTube”

[44] Lewis, Rebecca. “Alternative Influence: Broadcasting the Reactionary Right on YouTube.” Data & Society, 18 Sept. 2018

[45] YouTube, “Continuing Our Work to Improve Recommendations on YouTube”

[46] https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/carolineodonovan/down-youtubes-recommendation-rabbithole